REPRESENTATION, DELIBERATION, AND AGONISM

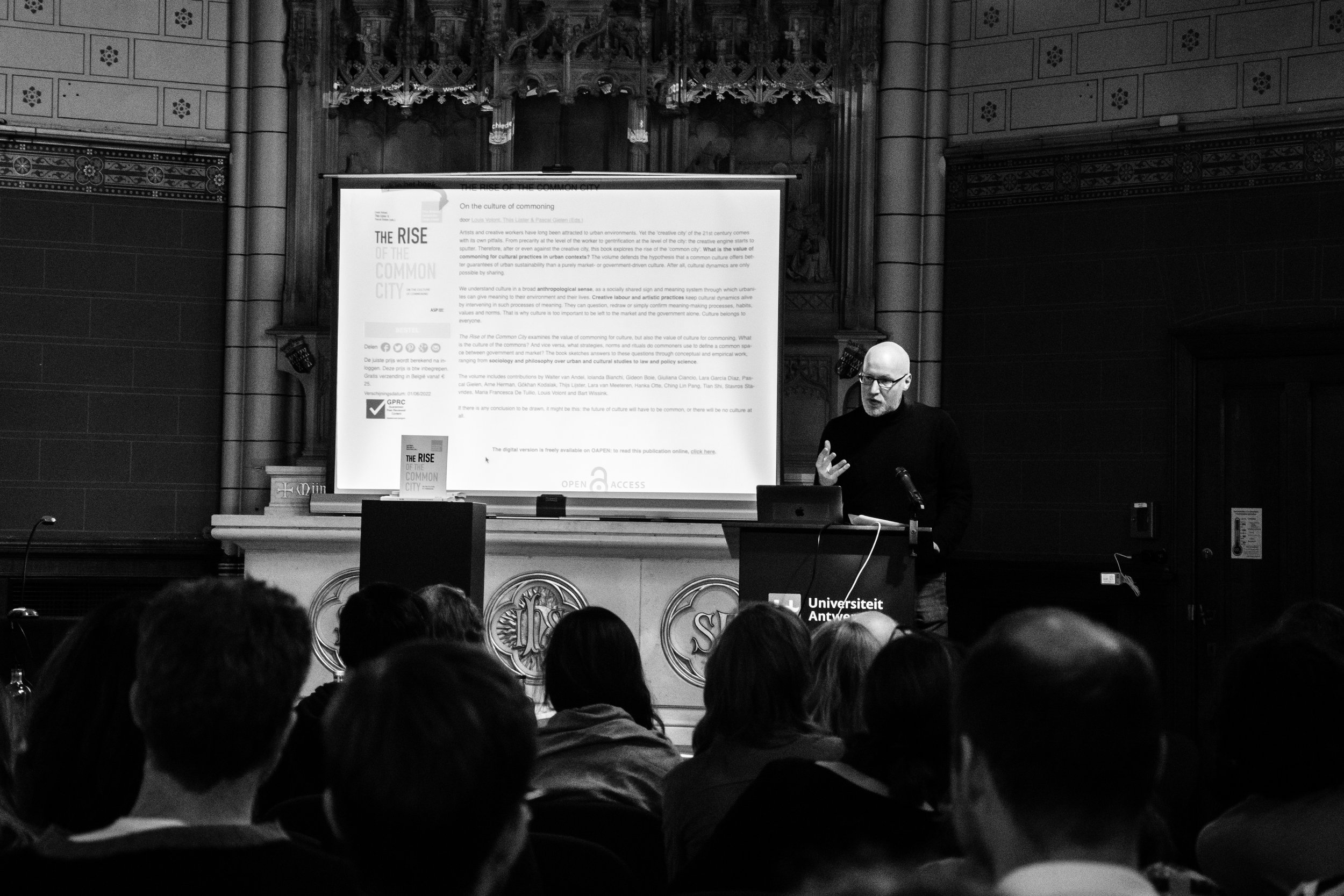

From: Otte & Gielen, ‘Captured in fiction? The art of commoning Urban Space’, The rise of the common city, 2022

“The CCQO team detected three forms of participation that can be traced within political science and political philosophy. The first one is the well-known representative democracy. This type of political participation occurred in still young nation states in the nineteenth century, together with the political emancipation of the bourgeois. It therefore fits well into the liberal philosophy that places the individual at its centre. This system is founded on the representation of the people through elections that are held every four or five years. In such a democratic order, a cultural policy on one hand serves to strengthen the identity and legitimacy of the nation state. It does so with national museums, theatres, libraries, and an official national language, statues and paintings of national heroes, and events that give the nation state historical foundation – in short, the national canon.

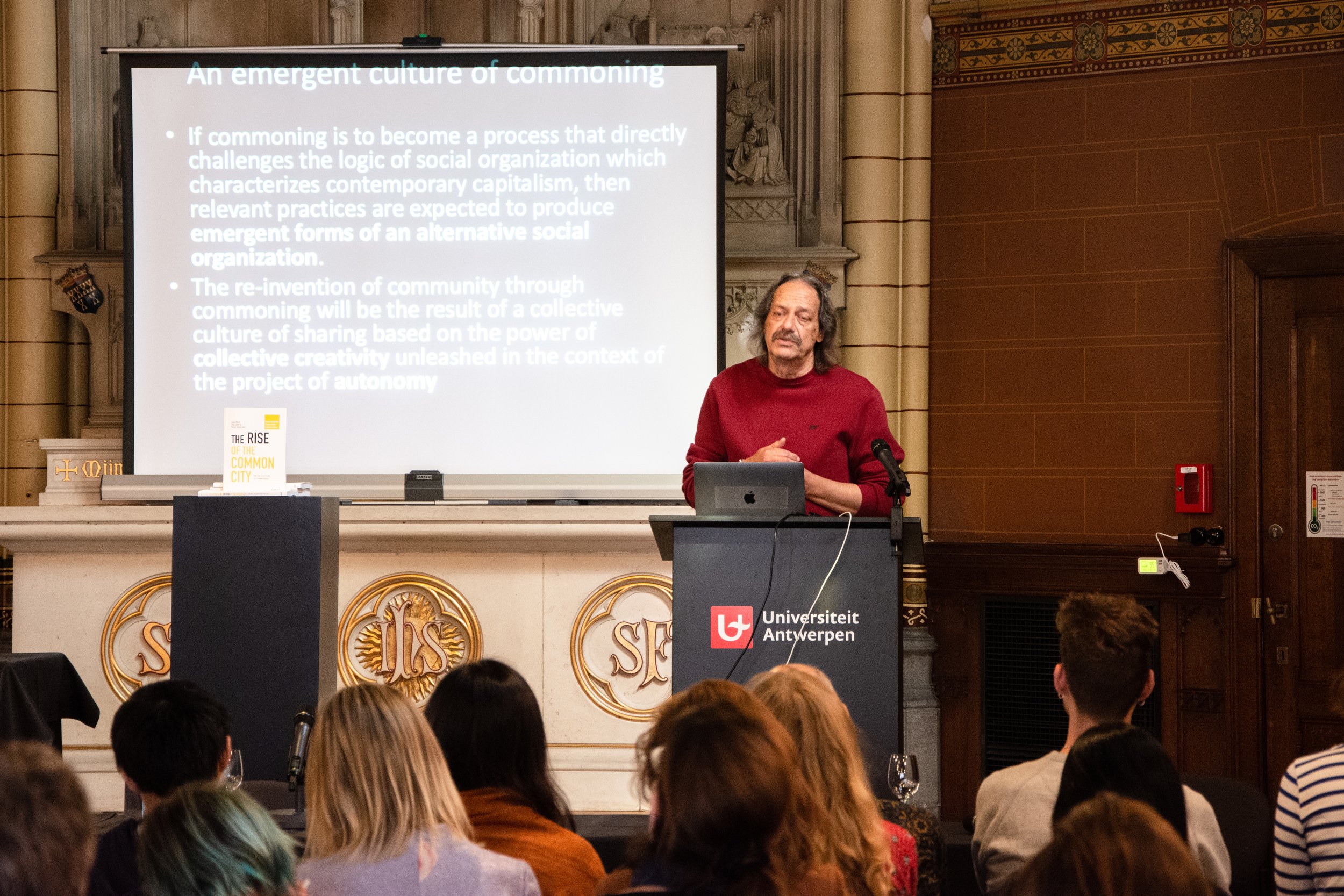

By the end of the 1960s, workers, artists, and students took to the streets to demand the democratisation of overly rigid and overly hierarchical state institutions and other institutes (parliament, university, museums). Debates, discussions, and negotiations were the basic ingredients of this second wave of participation, also referred to as deliberative democracy. Strongly influenced by Jürgen Habermas’ ‘communicative action’ (Habermas, 1981) and his analysis of the origin of the public space (Habermas, 1962), this form of democracy assumes that consensus can be arrived at on the basis of debate and rational arguments. Whereas in a representative democracy the civil struggle focuses on the quantitative vote (the number of votes is what counts), in a deliberative democracy the struggle is about the quality of that vote (what counts is what one says). Thus, the attention shifts from political democracy to cultural democracy. Just like a representative democracy, a deliberative democracy also has its exclusion mechanisms. The riots with so-called ‘random violence’ that broke out in American and European cities since the 1990s are often explained as being a reaction to these exclusion mechanisms. Up to and including the Occupy Movement, these protests are often seen by both politicians and mainstream media as ‘random’ or ‘senseless’, either because the ‘rioters’ simply pose no political demands or because these demands cannot be understood unequivocally (such as in the case of the Indignados). Such eruptions can however be seen as symptoms of the fact that—both within a representative and a deliberative democracy—certain segments of the population are not being heard. These are primarily groups with little education, or immigrants who do not speak the national language or don’t use the ‘proper’ (i.e., white, middle- class) vocabulary. It is one of the reasons why political philosophers and sociologists such as Chantal Mouffe, Ernesto Laclau, Jacques Rancière and Manuel Castells point out the civil and political importance of affects and emotion for a democracy. This brings us to a third form of participation, which, inspired by Mouffe, we call ‘agonistic’ (Mouffe, 2013). An agonistic democracy assumes—in line with Oliver Marchart (Marchart, 2007)—that democratic politics is ‘post-foundational’. This means that there is no foundation for power, such as God is in a theocracy or the majority is in a representative democracy, or a ratio is in a deliberative democracy. There can be consensus in a democracy about who can be in power and how this power can be obtained but an agonistic model assumes that this consensus is the product of hegemony. This means that the consensus arrived at is always that of a specific, privileged group that has obtained the control of power in a society. However, by suggesting that this consensus is not that of a certain power faction but of society as a whole, the opinions and cultures of subaltern groups and other alleged minorities are obscured and excluded. An agonistic democracy now assumes that consensus never applies to the whole of society and therefore can always be contested. In other words, dissensus is always possible. Characteristic for the civil struggle after this ‘affective turn’ is that it focuses on doing, on performance. An agonistic political model assumes that in addition to the vote—either quantitatively or qualitatively—there are also other forms of democratic participation. Democracy is therefore not limited to a proper debate in public or civic space, but translates itself in acting in civil space. And it is exactly here that art and cultural codes may play a crucial part. After all, artists have the talent and training to express themselves in other ways than through rational arguments. Expression in visual language, dance, music but also using an idiosyncratic vocabulary or presenting an alternative narrative are part of the core business of the arts. An agonistic cultural policy will therefore primarily create the conditions (cf. Rancière) for making (as yet) invisible, inaudible, and unutterable democratic demands visible and audible.

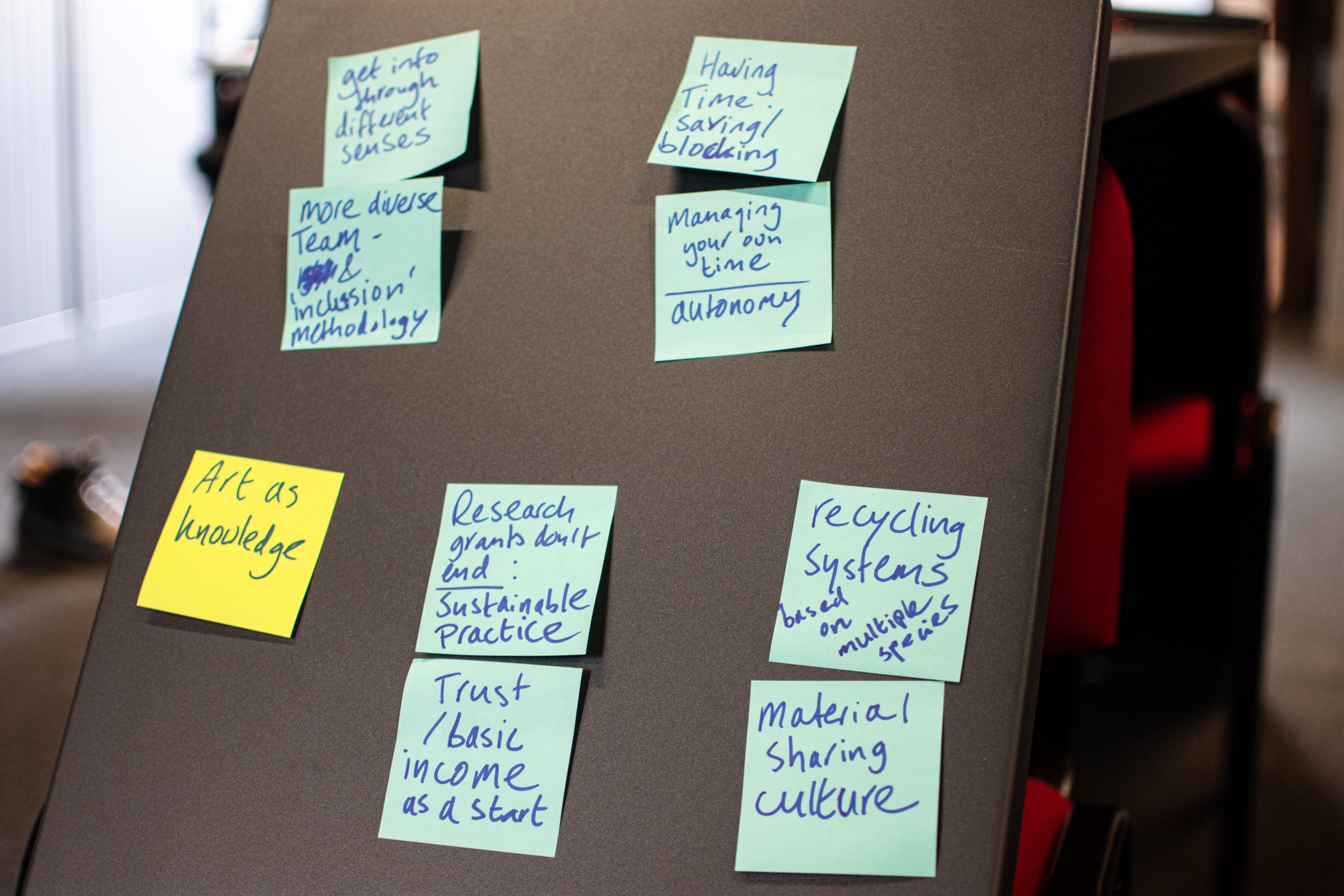

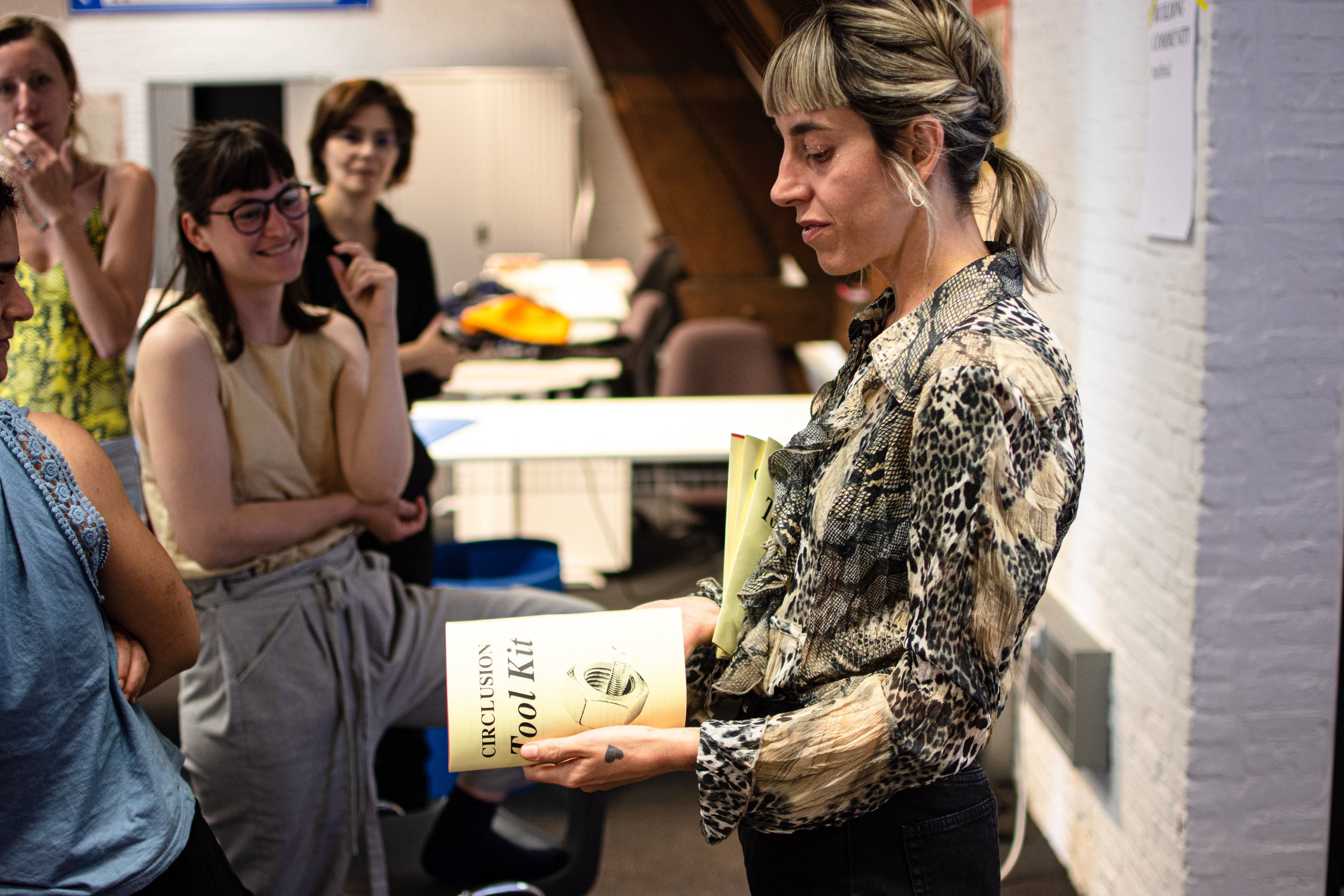

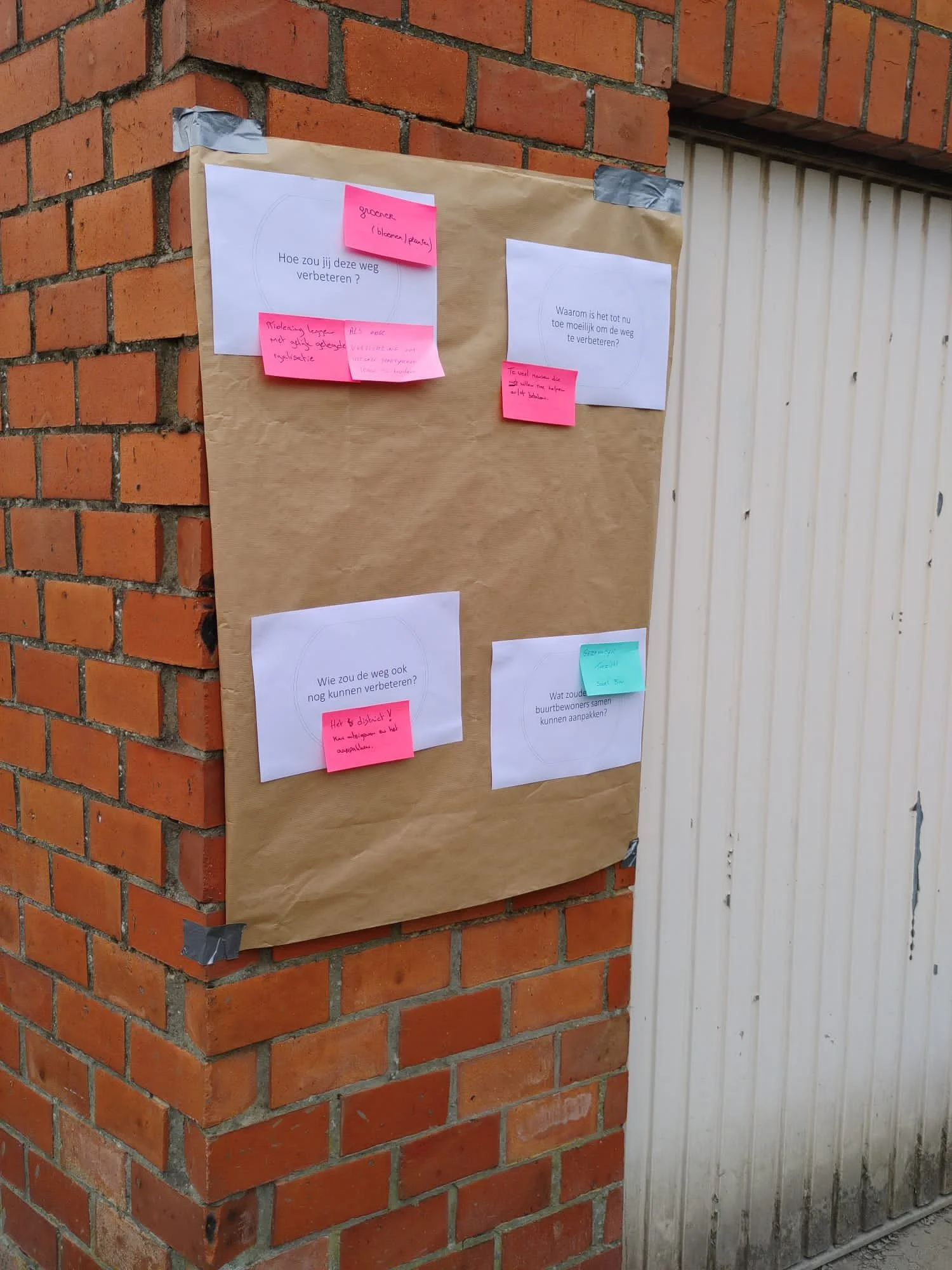

One of the demands and practices that, for the past thirty years, have remained unseen, and has also been repressed and suppressed, is that of the commons. Commoning in fact is a form of participation whereby commoners give form to their (social) environment by collective self-management of resources. To achieve this, commoners use competencies that are required in both a deliberative and an agonistic democracy. In addition to ‘doing’; for example, setting up an organisation, a blog, a platform, or developing rules, a lot of discussion and negotiation takes place (such as in assemblies), among commoners. Although commoners will vote every once in a while, in order to arrive at a decision (representation), the emphasis is on deliberation and agonistics (cf. supra). Especially the development of common initiatives rests on this participative model. Commoning practices tend to develop particularly in domains for which governments show no interest or where they fail to act and where market parties do not or not yet see, potential for profit. This third space between state and market is that of the civil initiative where citizens take matters into their own hands.

![20220308_071213[1].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59609b228419c269d9b95c1b/1670859322082-UKG7K6OFR13VOE2K0JPI/20220308_071213%5B1%5D.jpg)