Op zaterdag 17 juni maakten we voor de tweede keer van onze open Algemene vergadering een '𝗔𝘀𝘀𝗲𝗺𝗯𝗹𝘆 𝗼𝗳 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗰𝗼𝗺𝗺𝗼𝗻𝘀'. We zetten de deuren van HAL 5 in Leuven open voor iedereen met interesse in commons, in al zijn facetten. We mochten geïnteresseerden uit gans Vlaanderen verwelkomen: geëngageerde burgers/commoners, ambtenaren, ondernemers, leerkrachten, sociale organisaties,

Met deze bijeenkomst wilden we nieuwe mensen ook laten kennismaken met Commons Lab als socio-culturele organisatie. Juni 2023 markeert de helft van onze eerste termijn als structureel gesubsidieerde organisatie door de Vlaamse overheid. We hebben samen over de werking van Commons Lab gereflecteerd een toekomstige plannen en dromen uitgestippeld. We hebben geluisterd naar de vragen, wensen en ideeën van onze leden en sympathisanten. En we hebben elkaar beter leren kennen tijdens de lunch en de receptie.

Kennismaking en “check-in”

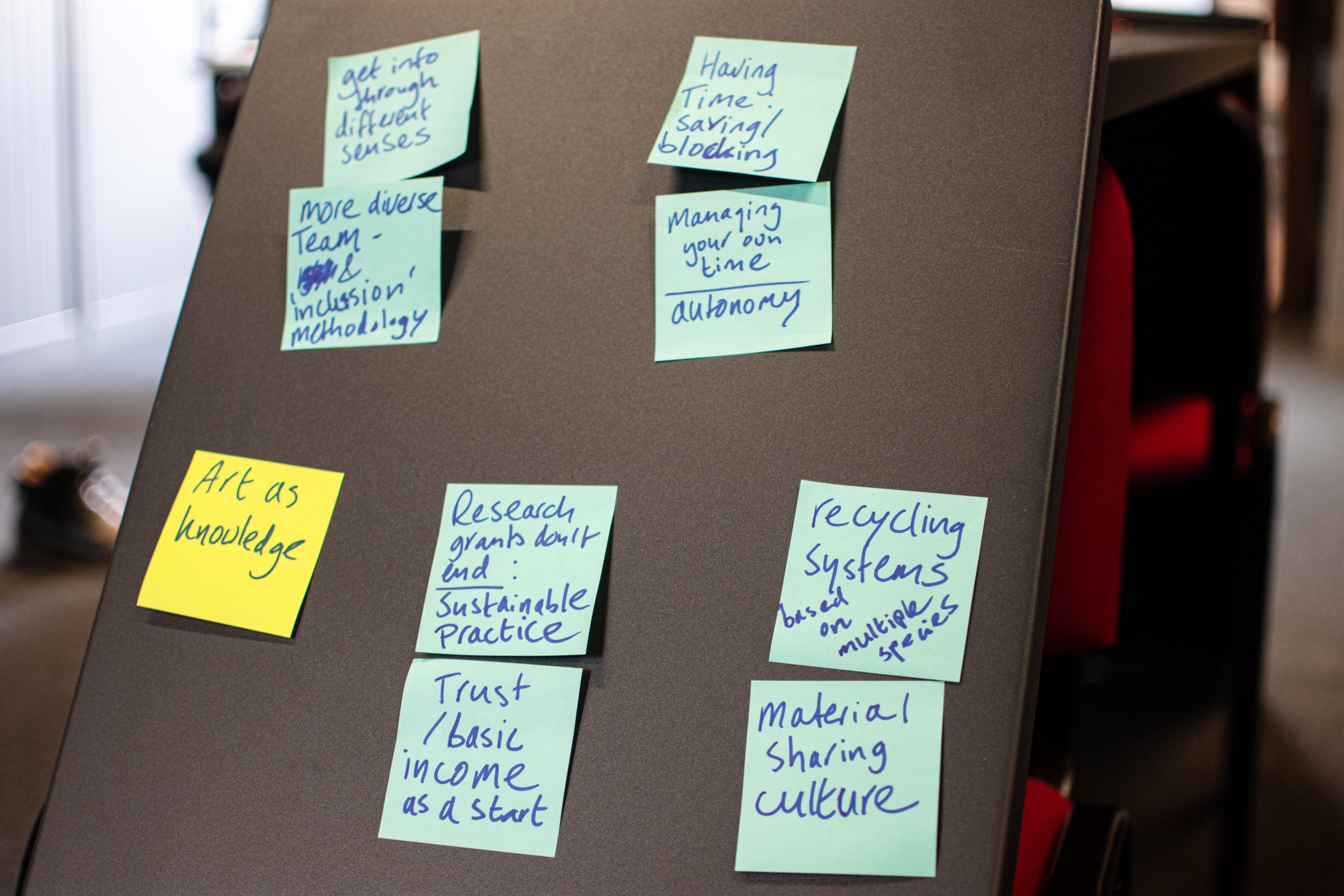

Na de ontvangst zijn we dag gestart met een interactieve kennismaking. De bedoeling was om elkaar zo in kleine groepjes te leren kennen. En tegelijkertijd om inhoudelijk het gesprek op te starten rond vrijwilligerswerking. De deelnemers noteerden ook hun verwachtingen voor de dag.

“De deelnemers hopen nieuwe, interessante mensen te leren kennen die gedreven bezig zijn en de wereld verbeteren, de organisatie beter te leren kennen, nieuwe inzichten te verwerven ”

Een vernieuwd Bestuursorgaan

Op 14 maart j.l. werd het Bestuursorgaan van Commons Lab vernieuwd. Jusra Baki, Tomas Uten, Ingrid Larik en Sofie Michiels kenden mekaar voorheen niet. Ze zijn allen al jaren als burger geëngageerd en superactief, in verschillende netwerken. Ze beschikken dus over heel wat ervaring, expertise en netwerken. Ze willen werken via een roterend voorzitterschap. Jaarlijks zal die rol overgenomen worden, Ingrid is als eerste Voorzitter. Ze zullen maandelijks samen komen.

Commons Lab als matchmaker binnen het Vlaams Commons transitie ecosysteem/community

Commons Lab begint als geen ander het ecosysteem van commoners, coöperaties, financiers, ondernemers, onderzoekers, overheden, experts van binnen en buiten te kennen. Dit ecosysteem rond de commons groeit aan een snel tempo incl. het aantal vragen dat bij CL binnen komt. Commons Lab wil nog meer mensen nog vaker en sneller doorverwijzen naar de juiste personen zodat zij en/of hun project vooruit geholpen wordt. Maar hoe kunnen we er voor zorgen dat het zo open en decentraal mogelijk verloopt, dat de community zichzelf beter leert kennen? Hoe kunnen we de kennis die uitgewisseld wordt door vraagsteller en antwoorder ook ruimer delen?

Tijdens de Assembly werd aangegeven om dit niet zomaar of volledig los te laten als Commons Lab:

We houden op die manier een vinger aan de pols.

Je moet sommige vragen er uit filteren.

Het is een schat aan informatie waarmee wij ook nieuwe experimenten etc. kunnen opzetten.

We willen graag mee groeien met het groeiend ecosysteem

Dit willen we doen door:

transparanter en sneller de vragen te delen (bvb. Via Fb groep, mail, website, nieuwsbrief,...).

regelmatig ‘Open commons fora’ te organiseren, rond specifieke thema’s, verspreid over Vlaanderen. Tijdens deze ‘Open commons fora’ krijg je de kans om te sparren met allerlei commoners, experts en organisaties. We nodigen mensen uit op maat van een specifiek thema.

ook grotere netwerkevents, specifiek gericht op netwerking met het ecosysteem, delen van kennis, ervaring, contacten. Zoals een Commons Festival, Commons Symposium, …

de mogelijkheden te onderzoeken om een open, online platform in gebruik te nemen dat meer zelfsturend werkt.

meer tijd te investeren in de opvolging: welke info wordt uitgewisseld en hoe kunnen we die info met gans ons ecosysteem delen? Hoe kunnen we de mensen die andere mensen vooruit helpen meer waarderen? Dit kan via website, nieuwsbrief, socials, ...

Het ecosysteem incl. Contactgegevens etc. meer delen (kan evt. ook via een digitale map)

Wat hebben we met de INPUT/OUTPUT van de AsSembly van vorig jaar gedaan?

Vorig jaar hadden we onze allereerste open Assembly in Timelab Gent! Toen hadden we 5 grote uitdagingen geformuleerd en in focusgroepen verder bediscussieerd.

We hebben er aan verder gewerkt en tot heden deze tools uit ontwikkeld:

Criterialijst voor projecten van Commons Lab

Vrijwilligersbeleid – one pager , intake sjabloon, afbakening vrijwilligersrollen

Verdeling van taken en rollen binnen Commons Lab middels sociocratie 3.0

Analyse en opmaak ‘profielen’ van toekomstige leden van Commons Lab

Vrijwilligerswerking van Commons Lab

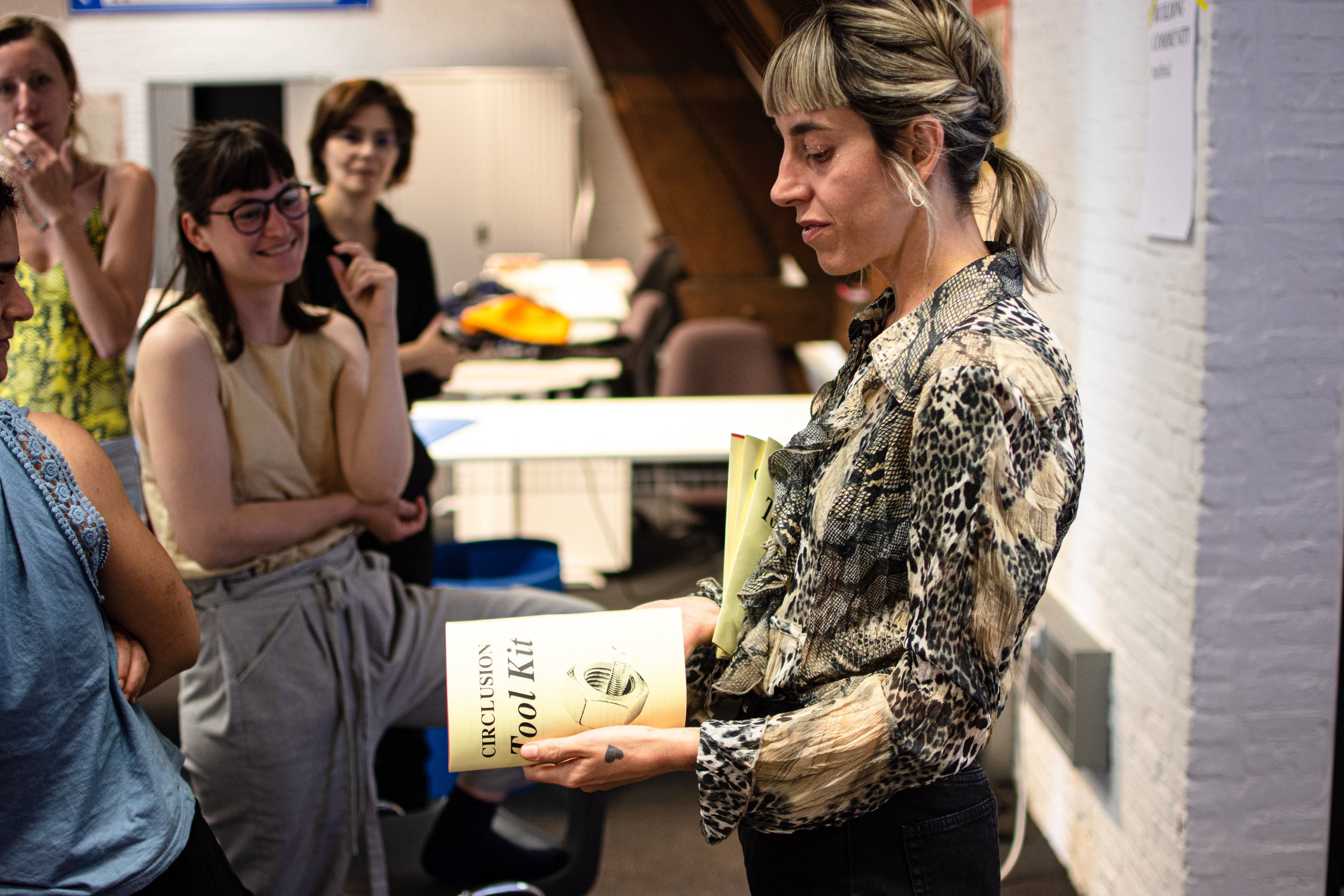

Er waren drie tafels met drie verschillende deelaspecten van het vrijwilligersbeleid van Commons Lab. De deelnemers schoven in drie groepjes aan en gaven telkens 20 minuten feedback op het voorstel.

“Mensen die zich engageren bij Commons Lab willen vooral: deel uitmaken van een netwerk van inspirerende mensen, nieuwe inzichten en kennis (over commons en de praktijk van commons) krijgen en delen, aan commoning doen tijdens informele momenten. ”

Ons netwerk heeft nood aan structuren om de kennis te delen en samen te komen:

idee fysieke plek: Fundament/Sint-Amandus als commons experiment

Er kwam ook de vraag om de website van Commons Lab actueel te houden en daar een ‘plek’ voor vrijwilligers te voorzien

Of een digitale platform waar vrijwilligers kunnen deelnemen

Via communicatiekanalen die ervoor geschikt zijn: open source, wiki model

(Verder) vermelde communicatiemiddelen: nieuwsbrief, Pebble, Kaizala

De vrijwilliger zou bij het intake gesprek de communicatie weg mogen kiezen (zijn gewenste communicatieweg).

Er kwam de vraag of de term ‘vrijwilliger’ goed past bij het commonsgedachtegoed. Er werd vermeld dat het belangrijkste is dat de vrijwilligers commonsengagment uitdragen.

Verdeling van taken:

Het is belangrijk dat naar de intrinsieke motivatie van het individu geluisterd wordt, dat verwachtingen goed afgestemd worden met de vrijwilliger en op tempo van de vrijwilliger gewerkt wordt.

De vrijwilligers zouden graag de taken mee verdelen. (Procedure ‘vragen aan Commons Lab’ en flow).

Het werd op gewezen dat de samenwerking met vrijwilligers co-creatief, met gedeelde verantwoordelijkheid en in vertrouwen zou moeten zijn.

Er werd het idee geformuleerd om per functie twee back-ups te hebben (indien iemand niet kan komen, ziek is, etc.).

De ambitie zou moeten zijn om twee vrijwilligers per maand te betrekken.

Indien er geen opdracht is voor de vrijwilliger: laten doorstromen naar andere organisatie, zoeken naar opdrachten bij partner organisaties.

Opleiding:

Opleiding in commons wordt erg belangrijk ingeschat. Vrijwilligers zouden aan alle vormingen die Commons Lab geeft en die medewerkers krijgen gratis kunnen deelnemen. Een idee is om aan elkaar opleiding te geven (zie boven: delen van kennis)

Bij de keuze uit opleidingen zou de leidraad moeten zijn wat nodig is voor de organisatie Commons Lab (vs. de vrijwilligers te laten kiezen).

“Fortaitaire kostenvergoeding” en betaling:

Als iemand en bepaalde expertise heeft vanuit zijn beroep dan zou Commons Lab deze persoon ervoor betalen.

Als de taak van de vrijwilliger veel tijd in beslag neemt (voorbereiding, avondwerk, of de uitvoering tijdens de werkuren van een andere job valt) is een forfaitaire kostenvergoeding aan de orde. Deze criteria zouden nog moeten gedefinieerd en afgestemd moeten worden.

De grens tussen opdrachten voor betaalde medewerkers en vrijwilligers is niet duidelijk afgebakend bij Commons Lab – daarmee moet Commons Lab voorzichtig omgaan. Oplossingen daarvoor: Voor elke vraag/opdracht betaling vragen (‘alles wat op maat gemaakt moet worden kost geld’). Commons Lab kan een deel van deze inkomsten zelf behouden of ‘enkel’ matchmaker zijn om de administratie beperkt te houden.

Kostenvergoeding (bv. reiskosten):

Voor een vrijwilliger is onkostenvergoeding een minimum.

Nazorg (bv. Regelmatig gesprekken voeren) en een bedanking blijken heel belangrijk.

Diversiteit (sleutelfiguren in de gemeenschappen zoeken)

Planning en prioriteiten Commons Lab 2023-2024

We zitten nu halverwege onze ‘ambtstermijn’ 2021-2025. We hebben 2.5 jaar heel hard gewerkt: we zijn van een Antwerps burgercollectief aan het groeien tot een professionele, Vlaamse socioculturele organisatie. Veel tijd en energie werd geïnvesteerd in organisatie-ontwikkeling en een verkenning in Vlaanderen.

Tijdens infosessies in mei hebben we onze voortgang in detail toegelicht. We kregen van de deelnemers en van enkele leden van CL de vraag om vanuit het team zelf met voorstellen te komen mbt prioriteiten en activiteiten voor de komende periode. We zouden daar vandaag dus een beeld van willen krijgen. Om morgen bij wijze van spreken samen te kunnen gaan werken aan de realisatie. We vinden het erg belangrijk om dat met z’n allen samen te gaan doen. We hebben in mindere mate denkers nodig, vooral doeners. We willen de komende maanden en jaren vooral heel resultaatgericht gaan werken, focus op collectieve actie. We hebben nog heel wat dromen. We hopen dat we komen tot ‘gemene’ dromen. En we hopen ook maximaal in teams te werken.

Open Commons fora

Het 'Open Commons Forum' is een laagdrempelige, informele, open samenkomst rond een specifiek thema op een bijhorende locatie. Een initiatiefnemer stelt het thema voor. Commons lab zal inhoudelijk, praktisch en financieel voor ondersteuning zorgen, incl. Interessante deelnemers trachten mobiliseren (+/-15). Ideeën en inzichten over een bepaald onderwerp in relatie tot commons worden uitgewisseld. Doel is om commonszaadjes te kiemen, te groeien, bloeien, of ‘kruis te bestuiven’. Een open commons forum kan gekoppeld/voorafgegaan worden aan een strategische interventie.

Zie als voorbeeld het Open Commons Forum in Schoten op 16 september, Open Commons Forum #2: ‘Over de Vaart’ • De vaart(kant) als gemeengoed — Commons Lab

Voorbeelden van thema’s:

Voedsel als commons in Gent

Commons en politiek

Zwemwater als commons -Kortrijk

Stilte als commons - Kempen

Kortrijk als commonsstad

Fruitige voedselbossen als commons-Hageland

Strategic interventions for the common good

Een strategische interventie for the common good is een laagdrempelige, creatieve, constructieve ingreep rond een specifiek thema op een specifieke locatie. Een initiatiefnemer wil iets mbt commons aankaarten, op de politieke en/of maatschappelijke agenda plaatsen. Mensen doen prikkelen, reflecteren, dialogeren specifiek mbt commons, rol van burgers, overheden, … Commons lab zal inhoudelijk, praktisch, financieel en juridisch voor ondersteuning zorgen. We zoeken evt. mee naar creatievelingen, kunstenaars, activisten met de nodige ervaring.

Voorbeelden van interventies:

Het Kortrijks burgercollectief LZSB breekt graag een lans voor vrij zwemmen en vrije en makkelijke toegang tot onze waterwegen met niet gemotoriseerde vaartuigen. Ze gaan in heel uiteenlopende Kortrijkse wateren wild zwemmen, nemen foto’s, delen die via diverse media.

Een wijk wil haar wijk toegankelijker maken door zelf een trage weg aan te leggen of te gaan beheren, open maken, ....

Rondreizend voedselbos

Bloembakken overal installeren in publieke ruimtes om het tekort aan groen, maar ook aan inspraak aan te kaarten

Een plein tijdelijk autovrij maken

Fietsenstallingen plaatsen op autoparkings

Een nieuwe, tijdelijke microhub installeren

Wij willen Spilkiekes in de publieke ruimte www.spilkiekes.be

Pop-up tegeltaxi in Antwerpen om de politiecodex aan te kaarten

Open Algemene Vergaderingen

Opleiding rond commons en coöperaties

Wandelingen, fietstochten, excursies langs commons en coöperaties

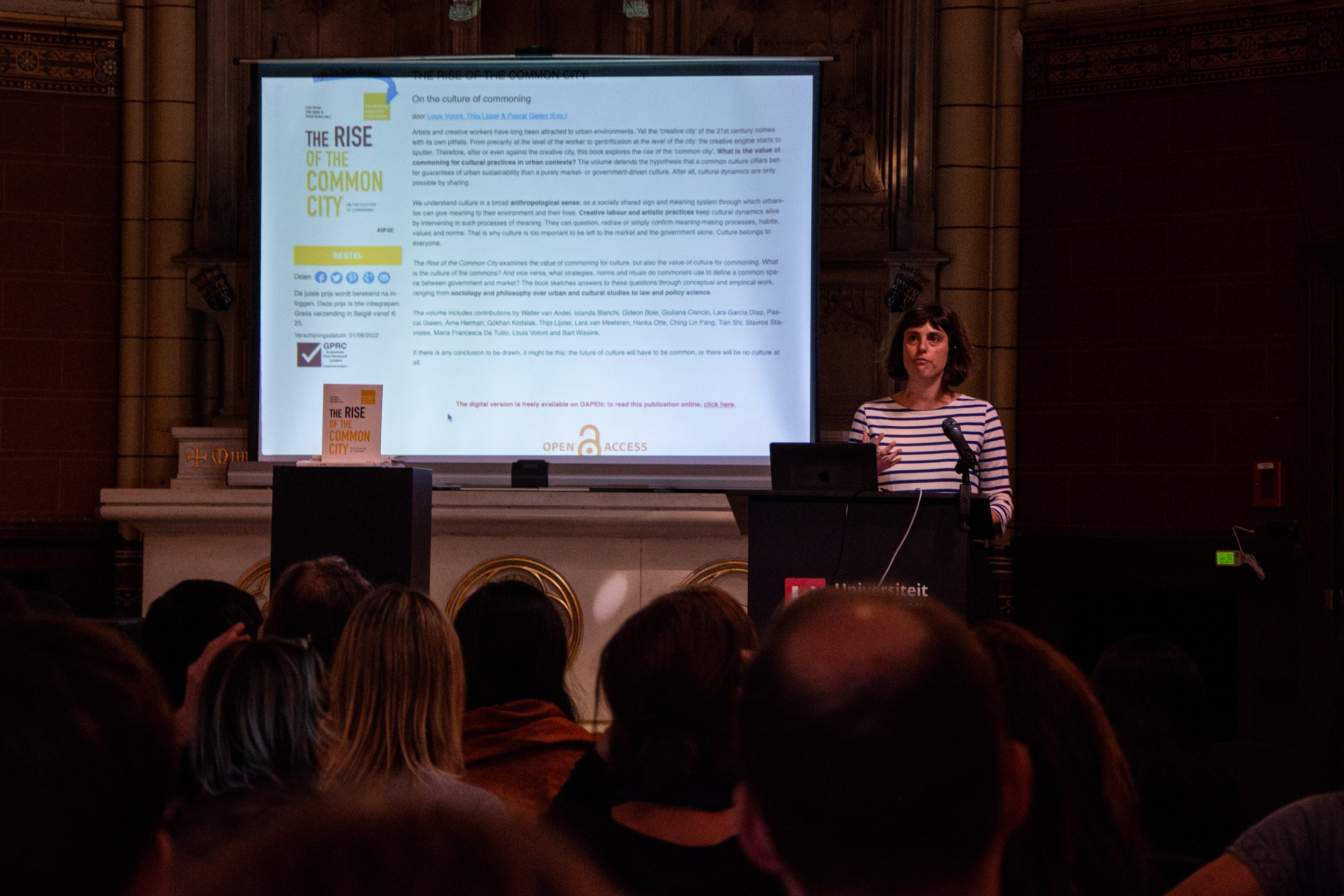

Boekvoorstellingen

Opleiding voor vrijwilligers CL

Leerreizen

Lezingen

Workshops

Intervisies/lerende netwerken

Inspiratiedagen/studiedagen

Vlaams Commons Symposium/Congres

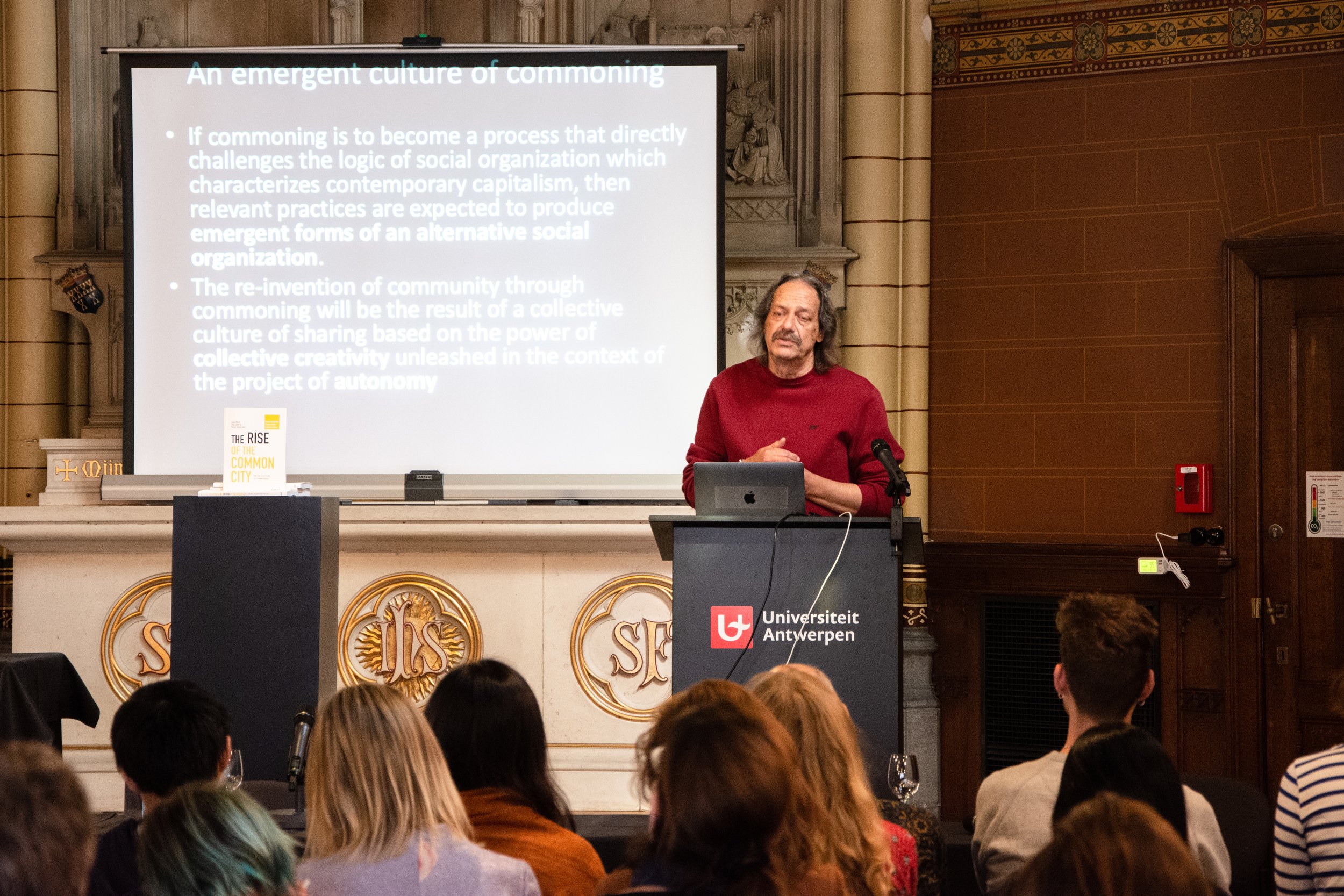

Het allereerste Vlaams Commons Congres organiseerde Commons Lab eind 2020 ism UAntwerpen, Oikos, stad Antwerpen. We brachten heel uiteenlopende commoners, experten, geïnteresseerden, ambtenaren samen. Vooral om kennis te delen en om na te denken over grotere vragen, uitdagingen, complexiteiten. We zouden opnieuw zo’n Vlaams Commons Congres kunnen organiseren om samen na te denken over en te schrijven aan het volgende Vlaams Commons Transitiemeerjarenplan.

Vlaams Commons transitie Festival

We dromen er van om de vele superinspirerende commoners en coöperaties uit gans Vlaanderen samen te brengen, op een spreekwoordelijk podium te hijsen, in een festivalachtige, informele, plezierige setting voor jong en oud. Open voor iedereen. Doel is om de community en de commons te versterken, commons op allerhande agenda’s te zetten.

We zouden dit kunnen combineren met het Vlaams Commons Congres, leerfestival, f-Festival van de verbinding,…

Samen uitchecken: Hoe heeft iedereen deze open Algemene Vergadering ervaren?

“De deelnemers hebben nieuwe, inspirerende mensen leren kennen, hebben goesting getankt, iets bijgeleerd. In de toekomst misschien meer aandacht en ruimte schenken aan de gekozen locatie. ”